There is a cardboard box in Genarlow Wilson's old bedroom.

The Bernstein FirmDespite lacking size, overachieving Genarlow Wilson was being recruited by several college football programs.

It rests on the floor of his empty closet, near the deflated football and basketball. It's filled with things he needed in his old life. Mostly, it's overflowing with recruiting letters, from schools big and small. A "Good luck on the SAT" postcard from the coaches at Columbia. From another Ivy League college, Brown, a note from the football coach: "You have been recommended to me as one of the top scholar-athletes in your area."

Despite lacking size, overachieving Genarlow Wilson was being recruited by several college football programs.

There's a questionnaire from the Citadel. A brochure from Elon. An envelope from Sewanee. College after college, all wanting the undersized but overachieving Genarlow Wilson to consider their football programs. One open letter, dated three months before everything in this box became a reminder of a life derailed, invites him to take a campus visit. It begins:

Dear Genarlow,

Here you stand, on the threshold of four of the most influential, challenging, and rewarding years of your life.

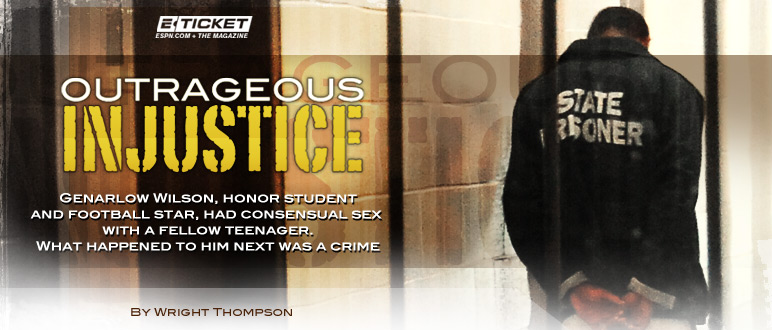

Being Inmate No. 1187055

Genarlow Wilson is standing on a threshold all right, at the end of the last hall of Burruss Correctional Training Center, an hour and a half south of Atlanta. He's just a few feet from the mechanical door that closes with a goosebump-raising whurr and clang. Three and a half years after he received that letter, he's wearing a blue jacket with big, white block letters. They read: STATE PRISONER.

He's 20 now. Just two years into a 10-year sentence without possibility of parole, he peers through the thick glass and bars, trying to catch a glimpse of freedom. Outside, guard towers and rolls of coiled barbed wire remind him of who he is.

Genarlow Wilson explains why he wouldn't take a plea bargain. Watch

Video courtesy of ABCNews Primetime live. Stay tuned to ABC News for updates on this story.

Once, he was the homecoming king at Douglas County High. Now he's Georgia inmate No. 1187055, convicted of aggravated child molestation.

When he was a senior in high school, he received oral sex from a 10th grader. He was 17. She was 15. Everyone, including the girl and the prosecution, agreed she initiated the act. But because of an archaic Georgia law, it was a misdemeanor for teenagers less than three years apart to have sexual intercourse, but a felony for the same kids to have oral sex.

Afterward, the state legislature changed the law to include an oral sex clause, but that doesn't help Wilson. In yet another baffling twist, the law was written to not apply to cases retroactively, though another legislative solution might be in the works. The case has drawn national condemnation, from the "Free Genarlow Wilson Now" editorial in The New York Times to a feature on Mark Cuban's HDNet.

"It's disgusting," Cuban wrote to ESPN in an e-mail. "I can not see any way, shape or form that the interests of the state of Georgia are served by throwing away Genarlow's youth and opportunity to become a vibrant contributor to the state. All his situation does is reinforce some unfortunate stereotypes that the state is backward and misgoverned. No one with a conscience can look at this case and conclude that justice has been served."

Wilson's mother, Juanessa Bennett, certainly doesn't understand. She has just bought a new house the next county over, hoping that a change of scenery might do her good. The past few years have been hard on her.

"You think, what in the world could I have done to God to make him punish me like this?" she says. "Am I that terrible a person?"

"It was like I had everything one day, and the next day I didn't have anything," Wilson says.

Her home feels empty without her son in it. He's not there to enjoy the five burgers for five bucks on Tuesday at the Sonic Drive-In, or chatting away on his telephone late at night. Now, she can only think about the past three years of their lives, and how everything is so different from before.

She points to a picture above her fireplace. There's a grinning 3-year-old boy in the frame, posing with big alphabet blocks.

"He was cute, huh?" she says, quietly.

She looks at the picture, but doesn't cry. There aren't many tears left. After it first happened, she says she cried so much she got an eye infection. Bumps broke out on her face, brought on by worry and grief.

"You need to stop stressing," the doctor told her.

She asked him how exactly she might do that.

"He didn't have an answer," Bennett says. Now, she's numb.

Now, she can only remember the boy he was and pray that when his ordeal is finally over, some of that boy will remain.

The image of a bright future dimming with each passing day is what infuriates so many people. Wilson should be held up as an example of a kid who was making it. His life should be protected by society, not destroyed. He was a good student, with a 3.2 grade point average. He was popular, the school's homecoming king, liked by students and teachers. He never got into any trouble with the law. He was a track and football star. His last two years, he was the defensive back assigned to cover Calvin Johnson, the former Sandy Creek High star who went on to Georgia Tech and is now projected as a top pick in the NFL draft. Wilson studied film, trying to figure out how to outsmart a better and taller athlete. He did well, coaches remember, limiting Johnson to four catches in two games.

Three years later, sitting in their office overlooking the field, finishing up another workday, Wilson's old coaches also remember a good but not great high school player who would have played college ball. They remember his last game, in the playoffs, way down in south Georgia. He got hit so hard on a kickoff return that he ended up spitting up blood on the sideline. The trainer shined a flashlight in his eye, figuring he had a concussion. Wilson grabbed his helmet, determined to go back in the game. He went to the hospital instead.

From drinking to smoking pot to acting like a cocky star athlete, Wilson now cringes at some of the mistakes he made in high school.

He admits he wasn't perfect. Far from it. He drank. He smoked pot. He'd been sexually active since he was 13. And a month or so after that final playoff game, he and some buddies were plotting a New Year's Eve bash. His mama heard them whispering in his bedroom that afternoon. She knew kids whispering usually meant trouble, so she went in and looked those boys up and down.

"Don't do anything stupid," she warned.

Something Stupid

Something Stupid Genarlow Wilson and his friends checked into the Days Inn right off Interstate 20. At some point in the night, according to court documents and evidence presented at trial, some girls came over to party with them. Bourbon and marijuana were consumed. One of the young men turned on a video camera.

Later in the evening, a 17-year-old girl began to have sex with the young men, first in the bathroom, then on the bed. Genarlow is captured on tape appearing to have sex with the girl from behind. Her hand is clearly visible on the floor supporting herself. Witnesses said she was a willing participant.

The next morning, the girl awoke in a stupor, wearing nothing but her socks. She called her mother and said she had been raped. Police came to the room after sunrise and took the revelers in for questioning. Genarlow had already gone home -- he didn't want to miss curfew -- but the video camera remained.

On tape, the cops saw a 15-year-old girl, a 10th-grader, performing oral sex on a partygoer and, after finishing with him, turning and performing the act on Genarlow. She was the instigator, according to her mother's testimony. Problem was, the girl was a year under the age of consent. Local prosecutors called the act aggravated child molestation, following the letter and not the spirit of the law, which was designed to prosecute pedophiles.

A week later, on the first day of the second semester of his senior year, the police went to the school and arrested the boys. Wilson was charged with four felonies and taken from the building in handcuffs. Not long before, he'd been in the newspaper for being all-conference in football. Now, he was on the front page, branded a rapist and child molester.

"It was like I had everything one day," he says, "and the next day I didn't have anything."

For the next eight months, Douglas County District Attorney David McDade, who likes to wear an American flag in his lapel and play to his law-and-order-loving base, dangled plea bargains. The other boys didn't want to risk a jury, and one by one each took an offer and went to prison, including the other football player arrested, Narada Williams, who accepted five years with the possibility of parole.

In Douglas County, according to law professors following about the case, admitting sins and begging forgiveness -- not insisting on your innocence -- is the road to mercy. Williams is already out of jail, in part because McDade wrote a letter to the parole board, praising Williams for being the first to plead guilty and "take his medicine." As for Wilson, McDade called him a "martyr" in the media.

If he had accepted the plea bargain, Wilson would've had to register as a sex offender and wouldn't have been permitted to live in the same house as his younger sister.

Wilson refused to admit to being a child molester. If he pled to or was convicted of any charge that put him on the sex offender registry, he couldn't live at home with his younger sister. He wouldn't accept that, so he waited for his trial.

The Saturday before it began, his last weekend as a free man, Wilson tried out for a local semi-pro football team. He wanted to be that other person once more, the one who could outrun all of life's problems. For two glorious hours, he sprinted and jumped and dived. When it was over, the coaches were impressed. They traded cell phone numbers, just another opportunity that would soon pass him by.

Two days later, in February 2005, Genarlow Wilson walked into a courtroom. Two charges already had been dropped, and it was clear from the first witness that the rape charge wouldn't stick either. The aggravated child molestation, though, was on tape. Genarlow tried to defend himself against the assigned prosecutor, Eddie Barker.

"Sir," Wilson told him, "you don't even know me. I understand you're just doing your job, sure, but I mean, how would you feel if you were my age and you were put on the stand with these serious charges at this young age? I have a little sister. Why would I molest anyone, sir?"

"I'm not on trial here, Mr. Wilson," Barker said. "You're the one who did these acts, not me."

The day before the trial was expected to end, in the last night he'd ever spend at his home, Wilson went to a church down the street and asked the preacher to pray with him. He awoke early the next morning. He knotted his tie carefully and went to the courthouse. The trial finished that afternoon, and the jury came back with "not guilty" on the rape but "guilty" on the aggravated child molestation.

He looked at the forewoman. She was crying, seeming to understand they'd just undone a promising future. Indeed, when the jurors found out there was a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence, several were incensed. The prosecution told them to write a letter, then moved on to the next case.

Genarlow Wilson put his head in his hands and wept.

Once identified as a promising football prospect, Wilson is now just known as inmate No. 1187055.

Deputies yanked him from his seat. Not long after, Prisoner 1187055 found himself in the predawn darkness, riding in a bus, surrounded not by his teammates but by murderers, thieves and rapists. Some were headed to the penitentiary for the second or third time.

A scared kid looked out the window as the bus chewed up pavement. He didn't know what it was going to be like, only that he didn't want to go.

Doing Hard Time

Wilson moves to the rhythm of the prison now, up early with the shift change, tidying his cell, sitting down to rest before chow, wearing white pants with a blue stripe. It has been 23 months.

These walls and bars haven't taken his youth, though. Not yet. When he smiles, it's the same one from that old photo on his mom's mantel. Bennett wonders how her son has managed to keep that light in such a dark place and how much longer he can hold out.

With nothing but time, he has taken stock of his old life. He doesn't like the person he was back then, the cocky star athlete with the world as his yo-yo. When he thinks about the kid on that videotape, with a Pittsburgh Pirates hat cocked just so, he cringes.

"It's embarrassing to me," he says. "You see yourself. ... 'Man, I acted like that?' "

He has followed his appeals from behind bars. He watched as the state legislature changed the law that put him there, then declined to make it retroactive, for reasons that still boggle the mind. That was a dark day.

He watched as B.J. Bernstein, his new attorney, filed a petition for writ of certiorari, asking the Georgia Supreme Court to review the case. The petition was denied, then set aside, then denied again, then appealed, then denied again. Those were darker days.

The first time the Supreme Court voted on Genarlow's case, it was 4-3. The four judges who voted against the black teen were white. The three judges who voted for him were black.

"I don't understand the Supreme Court," Bennett says. "Do these people not have hearts? Can they not look and see this isn't right?"

Wilson's attorney, B.J. Bernstein, is working pro bono to try to get her client out of prison.

In its decision, the Supreme Court called Wilson a "promising young man," a paragraph that he has read a thousand times. All the e-mails Bernstein gets in support of him, he has those, too. He reads them over and over, reminding himself that he once had a future and, one day, might have it again. It's not easy.

Other people's lives have moved on.

He has corresponded with Williams, his co-defendant and old high school teammate. Williams is enrolled in college now.

Wilson sat in prison and watched Calvin Johnson, the guy he once covered, become the best college receiver in the country and a soon-to-be millionaire.

"That has made my ambitions higher," Wilson says. "That makes me want to succeed even more because I don't want to be left behind."

The Halls of Power

In Atlanta, Bernstein makes her rounds at the state capitol. It's the first day of the legislative session and men in power ties click their wingtips over marble floors, lobbyists back-slapping each other in their little groups.

"He's sitting in jail," she says. "He's in jail every day they're sitting around chatting."

Instead of an Ivy League school, Wilson went straight from Douglas County High to Burruss Correctional Training Center.

When Bernstein met Wilson, who had a different attorney for the trial, she saw that light in his eyes and didn't want prison to extinguish it. Truth is, she's a rescuer. One of her cats she found on the interstate. She stopped her car in the rain on a six-lane highway to save it. In her heart, she wants to save the world, starting with Genarlow Wilson. That means working pro bono, even as every small check the firm earns goes straight into the operating account. That means figuring out this strange power-brokers' dance.

It's frustrating work. No one involved believes Wilson should be in jail for 10 years.

The prosecutors don't.

The Supreme Court doesn't.

The legislature doesn't.

The 15-year-old "victim" doesn't.

The forewoman of the jury doesn't.

Privately, even prison officials don't.

Yet no one will do anything to free him, passing responsibility around like a hot potato. The prosecutors say they were just doing their job. The Supreme Court says it couldn't free him because the state legislature decreed the new law didn't apply to old cases, even though this case was the entire reason the new law was passed. One possible explanation is that Bernstein, an admitted neophyte at backroom dealing, simply didn't know enough politics to insist on the provision. That haunts her.

As an honor student, football star and homecoming king, Wilson conquered challenges in high school ... but he now faces an uncertain future.

The legislature still could pass a new law that would secure Wilson's freedom, so Bernstein is pushing hard for that. One such bipartisan bill was introduced this week, pushed by state Sens. Emanuel Jones, Dan Weber and Kasim Reed. This is Wilson's best shot. "I understand the injustice in the justice system," Jones says, "and when I heard about Genarlow and started studying what had happened, I said, 'This is a wrong that must be righted.' Everyone agrees that justice is not being served."

Afterward, Bernstein can file a writ of habeas corpus, which could get him out of jail, but those are legal Hail Marys. She's a true believer, but if the legislature denies this latest attempt, she knows she might not be able to save Genarlow Wilson. Until it's over, nothing's off the table. Not even simple positive thinking. Sitting at a midtown-Atlanta Chinese restaurant on a lunch break from all the political wrangling, she picked up her fortune cookie, smiled thinly and said, "Gimme a good one: Genarlow will be free."

She's still working every angle, from the capital to cookies, riding up an elevator to the 53rd floor of an Atlanta high-rise to see David Balser, the attorney who got Marcus Dixon out of jail. The Dixon case was similar: As an 18-year-old, he had sex with a 15-year-old girl and was sentenced to 10 years before the conviction was overturned.

Sitting in a conference room overlooking Stone Mountain, Balser listens. The light shines off his gold cufflinks, the high-thread-count shirt hanging perfectly off his shoulders. He's got a little salt in his pepper and a Virgin Islands tan. They talk media strategy. They talk last-ditch plans, including a constitutional amendment returning pardon power to the governor. When they're done, Balser walks Bernstein to the elevator.

"I think less is more, B.J.," he says. "You've got to get him out and solve the world's problems after that. Just get him out."

"I'm trying," she says.

"I have faith in you," he says.

Letter of the Law

Every story needs a villain, and in this one, the villain's hat has been placed squarely on the head of Barker, the prosecutor and a former college baseball player. Barker doesn't write the laws in the books to the left of his desk. He simply punishes those who break them.

"We didn't want him to get the 10 years," he says. "We understand there's an element out there scratching their heads, saying, 'How does a kid get 10 years under these facts?' " In Barker's eyes, Wilson should have taken the same plea agreement as the others. Maintaining innocence in the face of the crushing wheels of justice is the ultimate act of vanity, he believes.

"I understand what he's saying," Barker says. "I think he's making a bad decision in the long run. Being branded a sex offender is not good; but at the same time, if it made the difference between spending 10 years as opposed to two? Is it worth sitting in prison for eight more years, and you're still gonna be a sex offender when you get out?"

Barker is quick to point out that he offered Wilson a plea after he'd been found guilty -- the first time he has ever done that. Of course, the plea was the same five years he'd offered before the trial -- not taking into account the rape acquittal. Barker thinks five years is fair for receiving oral sex from a schoolmate. None of the other defendants insisted on a jury trial. Wilson did. He rolled the dice, and he lost. The others, he says, "took their medicine."

While Bernstein works on every possible legal solution, the Douglas County District Attorney's Office has the power to get Wilson out of prison. If the prosecution wanted, this could all end tomorrow. The D.A.'s office says Bernstein hasn't asked. Bernstein says she has. Not that any legal he said/she said matters. Only the prosecutors' opinion does, and according to at least one legal expert, prosecutorial ego is more of a factor in this case than race. The folks in Douglas County are playing god with Genarlow Wilson's life.

"We can set aside his sentence," Barker says. "Legally, it's still possible for us to set aside his sentence and give him a new sentence to a lesser charge. But it's up to us. He has no control over it."

The position of Barker and the district attorney, McDade, who refused to comment, is that Wilson is guilty under the law and there is no room for mercy, though the facts seem to say they simply chose not to give it to Wilson. At the same time this trial was under way, a local high school teacher, a white female, was found guilty of having a sexual relationship with a student -- a true case of child molestation. The teacher received 90 days. Wilson received 3,650 days.

Now, if Wilson wants a shot at getting out, he must throw himself at the prosecutors' feet and ask for mercy, which he might or might not receive. Joseph Heller would love this. If Wilson would only admit to being a child molester, he could stop receiving the punishment of one. Maybe.

"Well," Barker says, "the one person who can change things at this point is Genarlow. The ball's in his court."

Hanging On To Hope

Back at Burruss, Genarlow Wilson is standing against the wall, looking out through the glass of the control room, peering between the bars, watching his attorney and another visitor leave. He has had plenty of people who want to talk to him, including a group of concerned legislators who plan on visiting this week, which finally feels like a real step toward freedom. Problem is, they always go home after an hour or two. He stays behind.

The worst is when his mom comes. She visited on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, bringing him news of the outside world and a smile. She told him about the new house she bought, just over the Cobb County line, finally out of Douglas. She doesn't want him moving back there when he's released. Saying goodbye, though, kills him. He watches her go and is taken back to his cell, where he can just imagine her in her car, imagining him in this prison.

Wilson is facing another eight years behind bars if his sentence is upheld.

"When she leaves, a part of me leaves," he says. "I just have to get myself back together because we've got a long way to go. I try not to think about doing the whole 10. I'm putting claims on going home this year."

Hope is all he has left. He believes in a system that has failed him. He believes in those powerful men down in Atlanta. He believes in the kindness of others, and in the skills of Bernstein. He lets her work, spending most of his days in the prison library, reading all the books he can. Sometimes, he pretends he's a character, living in a fantasy world, not in a cellblock.

When the weather's nice, he can run laps around the yard, as if he's still on a football field, chasing down future first-round picks. The burn in his lungs feels like a time long past. It feels like freedom.

He looks through the windows just a moment more, sadness in his eyes, then turns around. Wilson stares down the hall of his prison, waiting on a day when he can go home.

"I've got a real good feeling about what's going on," he says. "I feel like 2007 is it. This is my year."

His mom has the house ready for him because any day now, her baby's coming back. She just knows it. Over past the dryer, that's his new bedroom. She picked it because it's close to the garage, so he could come and go as he pleases. She thought he deserved that.

Everything's set, in case it's tomorrow. She left the rapper posters rolled up, figuring a man would be coming home. She set out his football trophies and his high school diploma, to remind him what he used to be. She hooked up a television and a stereo. An alarm clock is on the nightstand, so he can get himself up for school. Even the bed is made.

The only thing missing is her son.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.

Comment