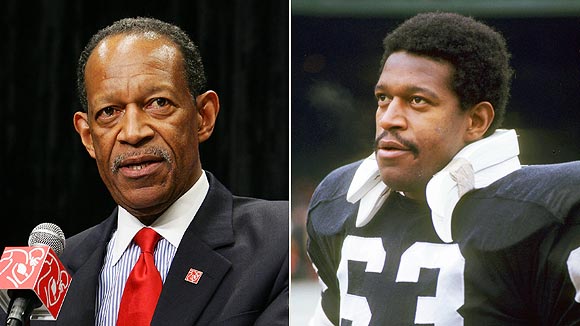

- Gene Upshaw was the NFLPA executive director since 1983. On the field, he was Hall of Fame guard for the Oakland Raiders from 1967-81.

He loaded his forearms with extra amounts of padding to prepare for the opposition. Offensive linemen, guards in particular, protect quarterbacks in relative anonymity. But Upshaw knew offenses needed to knock people over to move forward. Upshaw knocked opponents down as well as any blocker who ever played in the NFL, and he didn't do it quietly.

Upshaw, who died of pancreatic cancer Wednesday night, took the same approach as a labor leader. Working with Ed Garvey, the first NFLPA executive director who brought up the notion of getting a revenue share for the players from owners, Upshaw verbally knocked down opponents of the union's efforts to advance. He talked tough and conceded little. If a strike were needed, Upshaw policed his union with a firm hand to prevent a group of 2,000-plus dues-paying members from turning into 2,000-plus individuals who would buckle under pressure.

As a player and union leader, Upshaw was all about team, all about protection and, most importantly, all about the game. His loss comes with the NFL at a crossroads after two decades of labor peace that Upshaw helped foster with retired commissioner Paul Tagliabue.

Without Upshaw -- the NFLPA executive director since 1983 -- the NFL is like a quarterback vulnerable to a blind-side blitz. There is no succession plan for the NFLPA. The plan for getting future labor peace was in Upshaw's mind because he had all the relationships and all the background to get a deal done.

Still, what can't be forgotten is a giant of a man who came out of the trenches of the Oakland Raiders' offensive line and stood tall in helping turn the NFL into sports' most profitable and successful operation.

I will never forget his "We are the game" speeches of the early 1980s. Garvey boldly asked owners for 55 percent of revenues. Upshaw demanded a partnership from an owners group that once had players be responsible for supplying some of their own equipment.

The strikes of 1982 and 1987 were devastating, but Upshaw eventually proved his point. Owners had the money, but players had the bodies. Money can't execute power sweeps and zone blitzes. Players did that. Although it took a court settlement in Minneapolis in 1993 to save the league, Upshaw, like a pulling guard, knocked enough owners off their feet and brought them into the modern era of professional sports.

Players were partners, and significant ones at that. From the tough labor fights of the 1970s and 1980s, the players emerged with free agency and a percentage of revenue. As it turned out, free agency, though owners fought against it, turned out to be one of the league's greatest marketing tools. The movement of players through the offseason allowed football to pass baseball for offseason interest. It allowed the NFL to grow at an unprecedented rate.

Often, the leaders who fight for change can't manage their victories. In business, the corporate raiders who fight proxy fights for control of a company sometimes can't run the operation because they create too many enemies.

Upshaw turned out to be different. He challenged owners for close to two decades, but once there was labor peace, he turned into a good partner. What Upshaw understood is that players, though invaluable to the game, are replaceable. The college draft produces new pools of replacements each spring, and coaches decide who stays and who goes. Only the strong survive in the NFL, and Upshaw understood that.

Unlike baseball with a 25-man roster and basketball with 15-man rosters, football is a physical sport that starts with a 53-man roster and the need for constant replacements because of injuries. Because of the need for many players, fully guaranteed contracts weren't part of the economic equation for the NFL. Upshaw understood that and worked with owners on creating competitively fair ways of operating the game.

He knew owners needed some protections for star players such as quarterbacks, so the franchise and transition tags were allowed as a trade-off for unrestricted free agency. More importantly, Upshaw understood owners needed to create new revenue to allow player salaries to grow, and that's where he let the union become a good partner.

Players made concessions from their percentage of revenues that helped in allowing the league to get new stadiums. Upshaw worked with owners on new revenue streams, and now the league has $7.6 billion of revenue, and the number could grow to $10 billion in 2010. The players get 60 percent of that.

Upshaw also never received the appropriate credit for listening to his players. In the 1980s, steroid use was rampant in all sports. To get a competitive edge, some players used steroids to get bigger and stronger than their competitors. A silent majority of players didn't want to risk damaging their bodies with steroids. Upshaw led the push for testing, which is why football was more than a decade ahead of baseball in trying to clean up steroid use.

Like a lifeguard, Upshaw spent his post-NFL career watching out for his union members. He made the union strong and the game better. His passing leaves the sport with a breakdown in protection. He will be missed.

In a sport of replaceable parts, Upshaw is the one who might be impossible to replace.

Source: espn.com